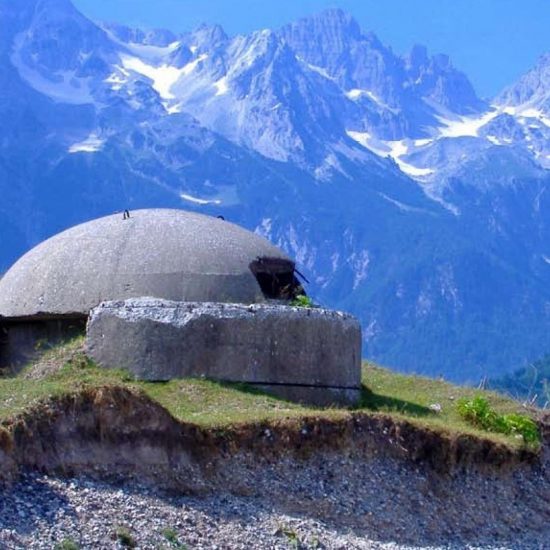

The legacy of Communism is still visible in Albania, where over 200,000 concrete bunkers dot the landscape. Built by the Enver Hoxha regime over the course of 40 years, these bunkers were designed to thwart a military invasion of the country. While they were of little defensive value to Albania, today they are an interesting attraction to the country’s visitors. Albania’s bunkers can be found in all different shapes, sizes and colors. Main attractions are The Anti-atomic Bunker Bunk'art 1 near Dajti Mountain and Bunk'art 2 near the Ministry of Interior , The Museum of Secret Surveillance of the infamous Sigurimi , Post Bllok monument in Tirana, the Bunker of Gjirokaster, Museum of Dictatorship Terror , Diocesan Museum in Shkoder.

When it seized power in November 1944, the new Communist government took immediate measures to consolidate its power.

In January 1945, a special people’s court was set up in Tirana under Koçi Xoxe (1917-1949), the new minister of the interior from Korça, for the purpose of trying Amajor war criminals.” This tribunal conducted a series of show trials which went on for months, during which hundreds of actual or suspected opponents of the regime were sentenced to death or to long years of imprisonment. In March, private property and wealth were confiscated by means of a special profit tax, thus eliminating the middle class, and industry was nationalized.

The communist leadership in Albania, always plagued by factional division, had split into two camps shortly after it took power. The rift between Tito and Joseph Stalin in 1948 gave Enver Hoxha a Soviet ally with whose support he could now act to preserve his own position, and he soon managed to eliminate his rivals. By June 1948, after several years of Yugoslav tutelage, Albania entered the Soviet fold.

Albania’s alliance with the Soviet Union had several advantages. The Soviets offered much food and economic assistance to replace the losses caused by the interruption of Yugoslav aid. They also gave the Hoxha regime military protection both from neighboring Yugoslavia and from the West at a time when the Cold War was at its height. As Albania had no common border with the Soviet Union, there was no immediate risk of direct political absorption, and the Albanian leadership was in many ways very mindful of preserving the country’s formal independence.

Integrated into the Soviet sphere, Albania entered a period of profound isolation from the rest of the world. “Ndërtojmë socializmin duke mbajtur në njërën dorë kazmën dhe në tjetrën pushkën” (We are building socialism with a pickaxe in one hand and a rifle in the other) was the slogan spread by the party to create a state-of-siege mentality that would stifle all opposition. By 1955, Albania had become the epitome of a Stalinist state, with Soviet models being copied or adapted for virtually every sphere of Albanian life.

However, when Nikita Khrushchev (1894-1971) denounced Joseph Stalin’s crimes and personality cult in a secret report to the 20th congress of the Soviet Communist Party in February 1956, Enver Hoxha decried revisionism. After some shrewd and ruthless political manoeuvering, he managed to overcome criticism of his own Stalinist policies and maintain power.

By December 1961, the Soviet Union broke off diplomatic ties with Albania, and Enver Hoxha, in search of a new patron, turned his attention to the Far East. The Sino-Albanian alliance, which was to last from 1961 until July 1978, radicalized political, economic and social life in Albania and isolated the country even more from Europe and the rest of the world. The People’s Republic of China provided Albania with much development assistance, including goods and low-interest loans, but this aid did not prove to be enough to promote economic growth.

In order to stem the tide of popular dissatisfaction with his rule, Enver Hoxha employed his usual tactic of counterattack, launching a Chinese-style campaign at the end of 1965 for the Arevolutionizing of all aspects of life in the country,” a campaign which coincided with the Cultural Revolution in China.What followed from 1973 to at least 1975 was a reign of terror against Albanian writers and intellectuals, comparable, in spirit at least, to the Stalinist purges of the 1930's. These years constituted the major setback for the development of Albanian culture. A series of purges kept other sectors of society, indeed the whole population, in a state of confusion and insecurity. With the demise of Enver Hoxha on 11 April 1985, political power fell to his successor Ramiz Alia of Shkodra, who ruled the country with a slightly gentler hand, although with no fundamental change of policy.

The foundations of the Communist system were finally shaken in early July 1990 when thousands of young Albanians risked their lives to seek political asylum in the German, Italian and French embassies in Tirana. Within half a year, the one-party dictatorship which had dominated all aspects of Albanian life for almost half a century had imploded. Political pluralism was introduced in December 1990, and the country’s first multiparty elections were held on 31 March 1991.Incredible as it now seems in retrospect, even to the Albanians themselves, orthodox Stalinism survived unscathed and unabated in Albania for a whole 37 years after Stalin’s death in 1953.

Though a definitive judgment on the Asocialist” period in Albania will have to be left to historians and political scientists of the future, the legacy of 46 years of Asplendid isolation” under Marxist-Leninist rule seems to have bequeathed the country with little more than universal misery and a backward economy. When one-party rule was finally done away with, there was virtually no intellectual leadership left to fill the void. Albania’s tiny socialist economy and its society lay in ruins. The beginning of the 1990s thus found the Albanian nation in a state of political, economic and social catastrophe.

Albania’s Bunkers by Robert Elsie

The legacy of Communism is still visible in Albania, where over 700,000 concrete bunkers dot the landscape. Built by the Enver Hoxha regime over the course of 40 years, these bunkers were designed to thwart a military invasion of the country. While they were of little defensive value to Albania, today they are an interesting attraction to the country’s visitors. Albania’s bunkers can be found in all different shapes, sizes and colors. There are some projects to convert the bigger ones into basic hotel rooms, while others have already been transformed by enterprising Albanians, transformed into beverage stands and burger shops. The bunkers have been built into the very fabric of everyday life in Albania, and you will undoubtedly see them during your visit. To understand why these bunkers were built is to understand the totalitarian, communist regime of Enver Hoxha. Perpetually paranoid of an invasion by a foreign power, the Hoxha dictatorship mandated the construction of a defensive infrastructure so elaborate that it would make it unacceptably costly for any would-be attacker. Building hundreds of thousands of concrete fortifications, despite nearly bankrupting the country in the process, was his coping mechanism for this paranoia. However, when we consider that Albania was never invaded during Hoxha’s tenure in power, one cannot help but wonder whether or not his bunker-building campaign wasn’t successful after all.

When it seized power in November 1944, the new Communist government took immediate measures to consolidate its power.

In January 1945, a special people’s court was set up in Tirana under Koçi Xoxe (1917-1949), the new minister of the interior from Korça, for the purpose of trying Amajor war criminals.” This tribunal conducted a series of show trials which went on for months, during which hundreds of actual or suspected opponents of the regime were sentenced to death or to long years of imprisonment. In March, private property and wealth were confiscated by means of a special profit tax, thus eliminating the middle class, and industry was nationalized.

The communist leadership in Albania, always plagued by factional division, had split into two camps shortly after it took power. The rift between Tito and Joseph Stalin in 1948 gave Enver Hoxha a Soviet ally with whose support he could now act to preserve his own position, and he soon managed to eliminate his rivals. By June 1948, after several years of Yugoslav tutelage, Albania entered the Soviet fold.

Albania’s alliance with the Soviet Union had several advantages. The Soviets offered much food and economic assistance to replace the losses caused by the interruption of Yugoslav aid. They also gave the Hoxha regime military protection both from neighboring Yugoslavia and from the West at a time when the Cold War was at its height. As Albania had no common border with the Soviet Union, there was no immediate risk of direct political absorption, and the Albanian leadership was in many ways very mindful of preserving the country’s formal independence.

Integrated into the Soviet sphere, Albania entered a period of profound isolation from the rest of the world. “Ndërtojmë socializmin duke mbajtur në njërën dorë kazmën dhe në tjetrën pushkën” (We are building socialism with a pickaxe in one hand and a rifle in the other) was the slogan spread by the party to create a state-of-siege mentality that would stifle all opposition. By 1955, Albania had become the epitome of a Stalinist state, with Soviet models being copied or adapted for virtually every sphere of Albanian life.

However, when Nikita Khrushchev (1894-1971) denounced Joseph Stalin’s crimes and personality cult in a secret report to the 20th congress of the Soviet Communist Party in February 1956, Enver Hoxha decried revisionism. After some shrewd and ruthless political manoeuvering, he managed to overcome criticism of his own Stalinist policies and maintain power.

By December 1961, the Soviet Union broke off diplomatic ties with Albania, and Enver Hoxha, in search of a new patron, turned his attention to the Far East. The Sino-Albanian alliance, which was to last from 1961 until July 1978, radicalized political, economic and social life in Albania and isolated the country even more from Europe and the rest of the world. The People’s Republic of China provided Albania with much development assistance, including goods and low-interest loans, but this aid did not prove to be enough to promote economic growth.

In order to stem the tide of popular dissatisfaction with his rule, Enver Hoxha employed his usual tactic of counterattack, launching a Chinese-style campaign at the end of 1965 for the Arevolutionizing of all aspects of life in the country,” a campaign which coincided with the Cultural Revolution in China.What followed from 1973 to at least 1975 was a reign of terror against Albanian writers and intellectuals, comparable, in spirit at least, to the Stalinist purges of the 1930's. These years constituted the major setback for the development of Albanian culture. A series of purges kept other sectors of society, indeed the whole population, in a state of confusion and insecurity. With the demise of Enver Hoxha on 11 April 1985, political power fell to his successor Ramiz Alia of Shkodra, who ruled the country with a slightly gentler hand, although with no fundamental change of policy.

The foundations of the Communist system were finally shaken in early July 1990 when thousands of young Albanians risked their lives to seek political asylum in the German, Italian and French embassies in Tirana. Within half a year, the one-party dictatorship which had dominated all aspects of Albanian life for almost half a century had imploded. Political pluralism was introduced in December 1990, and the country’s first multiparty elections were held on 31 March 1991.Incredible as it now seems in retrospect, even to the Albanians themselves, orthodox Stalinism survived unscathed and unabated in Albania for a whole 37 years after Stalin’s death in 1953.

Though a definitive judgment on the Asocialist” period in Albania will have to be left to historians and political scientists of the future, the legacy of 46 years of Asplendid isolation” under Marxist-Leninist rule seems to have bequeathed the country with little more than universal misery and a backward economy. When one-party rule was finally done away with, there was virtually no intellectual leadership left to fill the void. Albania’s tiny socialist economy and its society lay in ruins. The beginning of the 1990s thus found the Albanian nation in a state of political, economic and social catastrophe.

Albania’s Bunkers by Robert Elsie

The legacy of Communism is still visible in Albania, where over 700,000 concrete bunkers dot the landscape. Built by the Enver Hoxha regime over the course of 40 years, these bunkers were designed to thwart a military invasion of the country. While they were of little defensive value to Albania, today they are an interesting attraction to the country’s visitors. Albania’s bunkers can be found in all different shapes, sizes and colors. There are some projects to convert the bigger ones into basic hotel rooms, while others have already been transformed by enterprising Albanians, transformed into beverage stands and burger shops. The bunkers have been built into the very fabric of everyday life in Albania, and you will undoubtedly see them during your visit. To understand why these bunkers were built is to understand the totalitarian, communist regime of Enver Hoxha. Perpetually paranoid of an invasion by a foreign power, the Hoxha dictatorship mandated the construction of a defensive infrastructure so elaborate that it would make it unacceptably costly for any would-be attacker. Building hundreds of thousands of concrete fortifications, despite nearly bankrupting the country in the process, was his coping mechanism for this paranoia. However, when we consider that Albania was never invaded during Hoxha’s tenure in power, one cannot help but wonder whether or not his bunker-building campaign wasn’t successful after all.